With its surfeit of hotpot joints and dessert bars it’s easy to forget that until quite recently restaurants in Chinatown were nearly exclusively of the Cantonese variety. This was certainly the case in 2006 when Shao Wei launched Barshu just across the road from the enclave on Soho’s Frith Street.

It was a bold move, especially given that it was the Shandong province-born businessman’s first foray into the restaurant world. Though there were some regional Chinese restaurants in less prime areas of the capital, few had experienced the hot and numbing delights of authentic Sichuanese cuisine.

“Many people thought there was no more to Chinese food than what was being served in Chinatown,” says Wei, who is equally dismissive of the Sichuanese restaurants that were trading in London when Barshu threw open its doors (it should be noted that there were some restaurants on these shores serving authentic Sichuanese cuisine at the time, not least the then The North-based Red Chilli).

“There was no proper mainland Chinese food in London at the time really. Some had heard of Sichuan because Cantonese restaurants often claim their spicier dishes are Sichuanese. But those dishes aren’t close to being authentic."

Positioning the restaurant close to, but not quite in, Chinatown was symbolic, Wei says. “I wanted to create something that was different to Chinatown, so being a little away from it made sense. Plus Soho was associated with good restaurants, and Chinatown wasn’t.”

Heat of the moment

Wei’s decision to pull no punches – initially overseen by Chinese food expert Fuchsia Dunlop, Barshu’s menu was authentically fiery in its delivery – and use better quality ingredients than his peers on the other side of Shaftesbury Avenue (Barshu was not and is not cheap) saw the restaurant achieve cult status virtually overnight.

Rave reviews were published in quick succession, with critics falling over themselves to recount the sweaty, guttural delights of real Sichuanese food, including Jay Rayner, Giles Coren, AA Gill and Faye Mashler, who - then at the Evening Standard - wrote that the restaurant had “completely changed the face of Chinese restaurants in the capital”.

She wasn’t wrong. Barshu was then and remains a landmark London restaurant that has helped pave the way for others looking to explore the many branches of mainland Chinese cuisine.

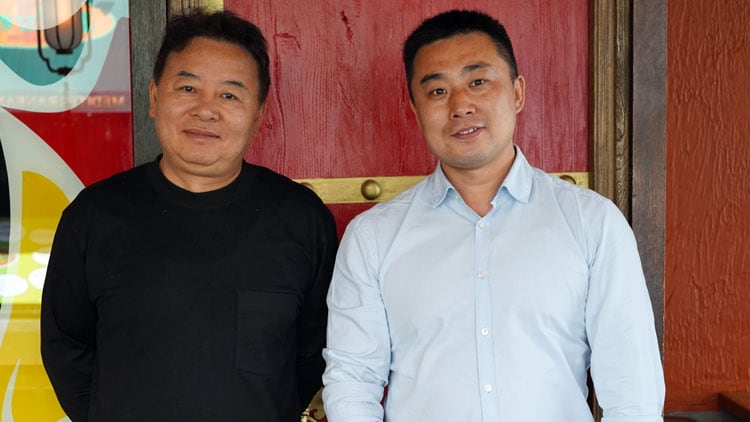

“Mr Wei had a big vision for Chinese food in this country,” says Winston Xu, who joined Wei’s wider business as operations director from hotpot juggernaut Happy Lamb just ahead of the pandemic. “Barshu uses the best ingredients and will always be the flagship of our operation but we want to continue to create restaurants that are different from what I call traditionally-run Chinese restaurants. We try and run our restaurants in a modern way and pay a lot of attention to branding and marketing. Many of our peers do not.”

Wei has since opened several critically well-received one-offs in the West End – including Barshan and Baiwei (both now closed) – and more casual growth brand Baozi Inn. But the pandemic has seen Wei and Xu refocus their attention on the group’s flagship.

Despite many requests, Barshu was one of the few Chinese restaurants in and around Chinatown to refuse takeaway orders. “It is a very premium restaurant which makes delivery difficult,” says Xu. “We wanted to keep standards high. But it was the only way to keep the business running, we had no choice. It’s been a big success but as a restaurant that’s already very busy for eat-in it’s been a challenge to manage things in the kitchen.”

Overhauling a cult classic

The success of the delivery offer and an eat-in market that remains challenging – a lack of visitors from China due to the country’s stringent quarantine rules has hit Chinese restaurants in the area hard – appears to have triggered a project to modernise the restaurant where it all started. The interior has been decluttered and brightened up and while some of the ornate carved wooden dividers that were a signature of the old design remain they now jostle for attention with bright murals. Though still reminiscent of the original, the 100-cover space is now more contemporary in feel.

The classic Sichuanese dishes with which the restaurant made its name remain but - presumably in a bid to broaden the restaurant’s appeal - a handful of dishes from other regions of China are now offered. Despite this, Barshu’s menu will still be largely unfamiliar to diners whose only experience of Chinese food is that offered by Anglo-Cantonese places.

Sichuan classics - including fish fragrant aubergines, twice-cooked pork; and whole fish floating in an oily sea of chillies and Sichuan peppercorns - are all present and correct. New dishes include stir-fried lobster with ginger and spring onions; and salt-and-pepper soft shell crab.

“The changes reflect what’s going on in China,” says Wei. “Many people are now moving away from very oily foods, for example. But the core of the menu will remain authentically Sichuanese.”

Dumplings legends

Replicating classic dishes is now less important at BaoziInn, which launched in 2008. The brand’s history is a little confusing. Its debut restaurant on Chinatown’s Little Newport - Baozi Inn (note the space) - offered affordable Sichuanese and northern Chinese cuisine including the eponymous large fluffy dumplings. It was almost canteen-like, offering multi-compartment trays that contained a complete Chinese meal, with main course options - including mapo doufu and a fiery stew of pork ribs and potato - usually served over rice.

But the BaoziInn restaurant sites that followed - one on the former site of Bashan in Soho’s Romilly Street and another near Borough Market - have taken a different tack with more diverse, contemporary menus that major on Cantonese-style dim sum and other types of dumplings, skewers and rice and noodle dishes.

“We wanted to create something that was more accessible for British people,” says Xu. “It is non-traditional. We combined a lot of different elements to create something more interesting that would look good on social media. But we do retain some Sichuanese and Hunanese dishes and influences. It’s a fusion of different things; for example some of our dim sum has fillings inspired by Sichuan.”

The original site was due to be brought in line with its older siblings but has yet to reopen following the pandemic.

Playing the market

Alongside its restaurant sites, the group has launched BaoziInn concessions at Market Halls locations including Victoria, Oxford Street, Canary Wharf and Intu Lakeside (the latter is no more following the food hall operator’s decision to close its only regional site just ahead of the pandemic).

“We noticed a gap in the market for Chinese food in these contemporary food market environments,” says Wei. “And when we launched our first one (in Market Halls Victoria) it soon became apparent there was a big gap in the market for good quality dim sum and other Chinese dishes that can be eaten on the go. We were one of the busiest stores.”

Such is the success of the brand at Market Halls, the group is currently on the hunt for a larger central London site to house BaoziInn’s production kitchen.

Using their noodle

Wei and Xu are now hoping to repeat the success of BaoziInn with a new casual restaurant format. Opened quietly on the Chinatown site that was once home to Baiwei earlier this year, Dot Line Noodle is billed as a test site.

Xu - who has led the development of the group’s latest concept - concedes that the Little Newport Street venue is not an obvious choice for what is ostensibly a fast-casual restaurant concept. “It’s an awkward site spilt over multiple rooms. Ideally it would be one big space with a counter but our resources were limited when it opened. The pandemic has been tough. We’ve got through it but Chinatown has been quiet, although things are a bit better now and we’re expecting visitors from China to return soon.”

Dot Line Noodles’ USP is the degree of customisation it offers. Customers choose the type of noodle, a broth and a topping. Options from the latter include beef shin steak, braised pork intestines and pig’s trotters. Ordered by marking a wipe clean menu, supporting items include cloud ear fungus with coriander, pot-stewed eggs, pork dumplings and a selection of salt-and-pepper-fried dishes.

Given the generosity of the portions prices are reasonable, with most noodle combos coming in around the £12 mark and most smaller plates under £5. If the brand is deemed suitable for roll out Wei will likely target high-footfall locations in London including the City.

The group is also on the hunt for a new location for Bashan, which launched round the corner from Barshu in 2009 but closed in 2018. “Barshan was successful but it confused people. While it was Hunanese rather than Sichuanese (the two provinces neighbour each other), the price point and style of food were quite similar and they were very near each other,” says Wei.

“But people are always asking me to bring it back. Hunanese cuisine is now very popular all over China so we would get a lot of Chinese customers. If we do bring it back it won’t be in Soho or Chinatown, though. I think West London could work well.”

The influential group has a fair bit on its plate, then. Times might be tough - before the pandemic Wei signalled he wanted BaoziInn to be the UK first truly national Chinese chain but growth plans have now been understandable scaled back - but this is still a business to watch closely.